Martin Luther on How Not to Tempt God During a Plague

It so happened that in the month of October in the year of our Lord 1347, around the first of that month, twelve Genoese galleys, fleeing our Lord’s wrath which came down upon them for their misdeed, put in at the port in the city of Messina. They brought with them a plague that they carried down to the very marrow of their bones, so that if anyone so much as spoke to them, he was infected with a mortal sickness which brought on an immediate death that he could in no way avoid.

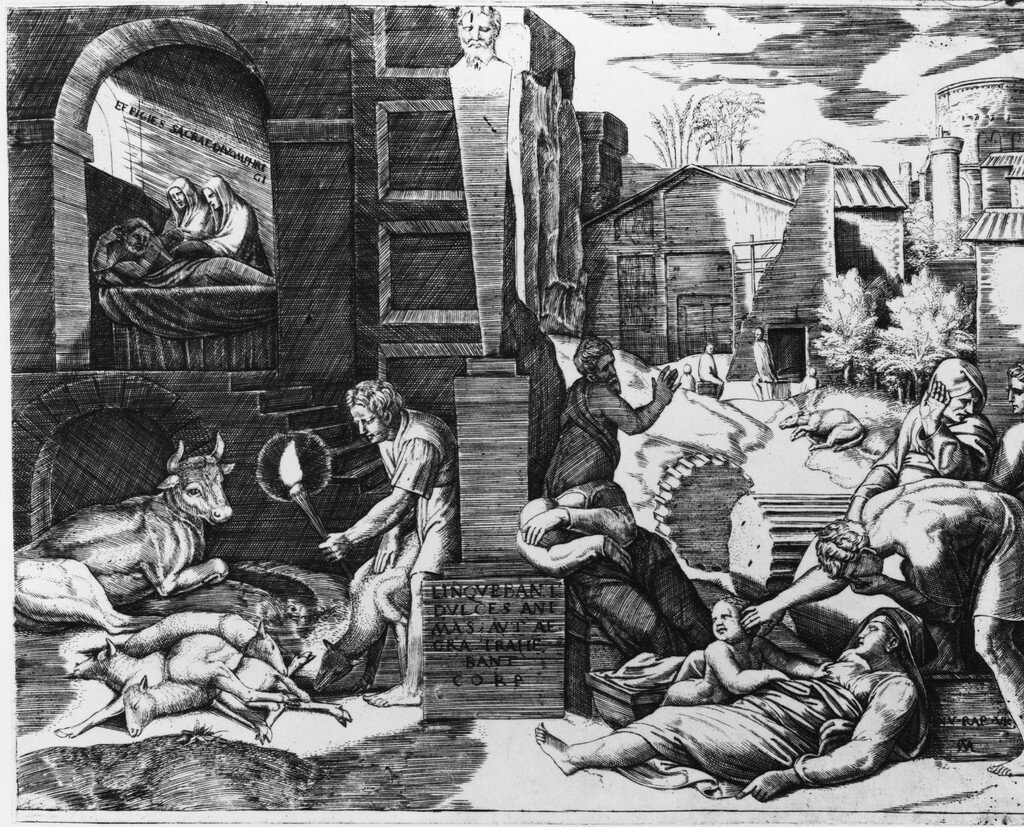

So begins one of the first historical accounts of the “Black Death” in late medieval Europe, written by the Sicilian chronicler Michele da Piazza. The plague was a truly terrifying pandemic. Modern estimates suggest that the disease may have killed as many as half those who contracted it, and when death came it was swift, agonizing, and utterly undignified. Consider this description, by another Italian eyewitness:

There are not words to describe how horrible these events have been and, in fact, whoever can say that they have not lived in utterly horrid conditions can truly consider themselves lucky. The infected die almost immediately. They swell beneath the armpits and in the groin, and fall over while talking. Fathers abandon their sons, wives their husbands, and one brother the other. In the end, everyone escapes and abandons anyone who might be infected. . . . And I, Agnolo di Tura, called the Fat, have buried five of my sons with my own hands.

Given the horror of these events, it’s not surprising that we find writers from this period wrestling with all sorts of difficult questions: how to avoid getting sick? How to avoid getting other people sick? How to continue maintain some semblance of normalcy when the world seems like’s been turned upside down? And above all: where is God amidst all this suffering and death?

These questions were even more pressing for those whose vocation called them to the front lines in the battle against the plague: physicians, who cared for the bodies of the sick; priests, who cared for their souls; friars, monks, and nuns, whose religious vows often required them to seek out the sick and care for their bodies and souls. And despite the grim observations of Agnolo the Fat, they didn’t all run away.

In the summer of 1527, the plague swept through Europe once again. But this time, it fell upon a society deeply divided—“polarized,” we would say—by the events of the Protestant Reformation. On top of all the old fears of death and social breakdown, perceptions of the disease were filtered through new layers of mistrust rooted in religious difference. Protestants regarded the plague as God’s judgment on Catholic decadence and idolatry; Catholics accused Protestants of weakening the unity of Christendom in a time of crisis. Both sides gleefully seized on examples of cowardice and other missteps to paint their enemies in the worst possible light.

By August of that year, the first victims of the plague were dying in the city of Wittenberg, where Martin Luther and his colleagues were laboring to reform the German churches. Just like many recent governments have done, the Elector John “the Steadfast” ordered a series of dramatic measures to combat the plague, including ordering the faculty of the University of Wittenberg—Luther included—to relocate to another city. Luther refused to leave. Together with his friend and colleague Johannes Bugenhagen, Luther stayed put in Wittenberg to care for the sick and the dying: preaching the Gospel, administering the sacraments, visiting the sick in their homes to provide pastoral and practical care, and eventually converting his own house (a former monastery) into a makeshift hospital.

By the time the plague died down in Wittenberg in the fall of that year, Luther was being criticized on both sides. Friends in the church and government believed he had been too reckless, ignoring the prince’s command to leave the city. But Catholic opponents, pointing to the aggressive measures the city had taken to isolate the sick from the healthy, accused the Lutherans of abandoning their flock in its time of greatest need.

Luther responded to these criticisms in an open letter titled, “Whether One May Flee from a Deadly Plague,” a masterpiece of pastoral guidance to a community in crisis. Luther’s main point may be summed up as follows: those in vocations with responsibilities to serve the common good—this would include city officials, doctors, and pastors, among others—are bound to remain in place. Christians are people who have been called by God, and the model for faithfully living out one’s calling is nothing other than Christ himself: “A good shepherd lays down his life for the sheep, but the hireling sees the wolf coming and flees” (John 10:11).

For those whose duties do not require it, however, Luther counsels balanced judgment and pragmatic common sense. On the one hand, Luther argues that fleeing from danger is not inherently wrong, and he multiplies examples from scripture to support this: Jacob fled from Esau, David fled from Saul, Paul fled from Damascus, etc., etc. On the other hand, Luther argues that the law of love compels us to help our neighbor in times of need, even when that help comes at risk to ourselves. “A man who will not help or support others,” Luther observes, “unless he can do so without affecting his safety or his property will never help his neighbor.” These are the ones to whom Christ will say, “I was sick and you did not visit me” (Matt 25:43).

Now, at this point one might object that times have changed since the sixteenth century. It’s not our job to care for the sick directly, especially not during a time of pandemic—that’s what the healthcare system is for. And Luther would actually agree. In point of fact, Luther’s Wittenberg was one of the first cities in Western Europe to appoint a full-time physician to care for the poor—at government expense! Luther saw this kind of arrangement as the ideal way of enacting the community’s obligation to care for needy, but he also recognized that in extreme circumstances, other measures may be necessary:

It would be well, where there is an efficient government in cities and states, to maintain municipal homes and hospitals staffed with people to take care of the sick so that patients from private homes can be sent there. . . . That would indeed be a fine, commendable, and Christian arrangement to which everyone should offer generous help and contributions, particularly the government. Where there are no such institutions—and they exist only in a few places—we must give hospital care and be nurses for one another in any extremity or risk the loss of salvation and the grace of God.

Strong words, these! But they are a strong reminder that whatever the early Protestant reformers like Martin Luther may have meant by teaching that salvation comes “through faith alone,” it certainly didn’t drive a wedge between our faith in God and the love and care we owe to our neighbors—far from it!

Most of Luther’s advice in this treatise is aimed at those fearful souls who were tempted to abandon their duties in a time of crisis. But he also acknowledges that there is another danger, what he calls “tempting God.” I will quote Luther at length here because it seems to me that his advice is particularly timely in our situation:

Others sin on the right hand. They are much too rash and reckless, tempting God and disregarding everything which might counteract death and the plague. They disdain the use of medicines; they do not avoid places and persons infected by the plague, but lightheartedly make sport of it and wish to prove how independent they are. They say that it is God’s punishment; if he wants to protect them he can do so without medicines or our carefulness. That is not trusting God but tempting him. . . .

No, my dear friends, that is no good. Use medicine; take potions which can help you; fumigate house, yard, and street; shun persons and places where your neighbor does not need your presence or has recovered, and act like a man who wants to help put out the burning city. What else is the epidemic but a fire which instead of consuming wood and straw devours life and body? You ought to think this way: “Very well, by God’s decree the enemy has sent us poison and deadly offal. Therefore I shall ask God mercifully to protect us. Then I shall fumigate, help purify the air, administer medicine, and take it. I shall avoid persons and places where my presence is not needed in order not to become contaminated and thus perchance infect and pollute others, and so cause their death as a result of my negligence. If God should wish to take me, he will surely find me, and I have done what he has expected of me and so I am not responsible for either my own death or the death of others. If my neighbor needs me, however, I shall not avoid place or person but will go freely, as stated above. See, this is such a God-fearing faith because it is neither brash nor foolhardy and does not tempt God.”

As our nation, our community, and our church continue to come to grips with the challenge of the COVID-19 pandemic, we hear a persistent drumbeat from all sides that we are in “uncharted waters.” In some ways, that may well be true. But Luther’s reflections on the plague are a good reminder that Christians have been dealing with deadly disease for centuries, and we have a body of accumulated wisdom to draw upon as we navigate these troubled waters. So let’s keep taking our potions (kale smoothies for me!), fumigating our houses (or at least using hand sanitizer), and shunning places where we’re not needed (social distancing) with a sense of urgency, like people who want to help put out a city on fire. This isn’t just good medical advice—it’s a spiritual necessity.